“I have no hesitation in saying that I have absolutely the whole of India at my back in wishing that the new city should be built in accordance with Indian sentiments. I do not by this mean that the town should be built of highly ornate or Hindu architecture, but that it should be a find broad style with a minimum of decoration, but that decoration should be of the purest and most ancient Hindu ornament.”

–Lord Charles Hardinge, British Viceroy of India, early 20th C

After the coronation of King George V in the year 1911, the British government decided to move its capital in India from Calcutta to Delhi. They had realized the strategic location of the city, and moreover, it was very close to Shimla, their summer capital. Lord Hardinge, the viceroy in India at the time was given the responsibility of establishing a new city in Delhi, New Delhi, that was to be the capital of the country. A team of several British architects, headed by Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker, was chosen to carry out the design of the new capital city.

A grand imperial capital

The vision was to build a grand imperial capital capable of holding its own against world-class cities like Washington and Paris. Now the dilemma the British rulers and architects faced was whether they wanted to go with the classical western style of architecture that would be sort of alien to the local populace, or whether to choose the indigenous style of architecture that didn’t reflect their own ethos and persona. Edwin Lutyens, in fact, firmly believed that Indians never had any real architectural style worth mentioning and they ought to adopt classic western style only. However, in the end, the will of Charles Hardinge prevailed and a hybrid style was adopted by Lutyens, Baker and their team of architects.

A hybrid imperial architecture breathing air of Indianness

Lutyens and Baker tried to make their style more rational and appropriate to its locale, incorporating elements from the Buddhist, Hindu and Mughal building vocabularies in their design. They combined the neo-classical with accents taken from Indo-Islamic and Buddhist architectural style. The endeavour was to satisfy the Indian sentiments by grafting certain decorations expressing local symbols, myths and history onto classic British architecture. Thus classical Indian elements like chhajjas (pavilions), stone jalis (lattices), shade-giving cornices and even Mughal gardens were extensively used.

A new beginning

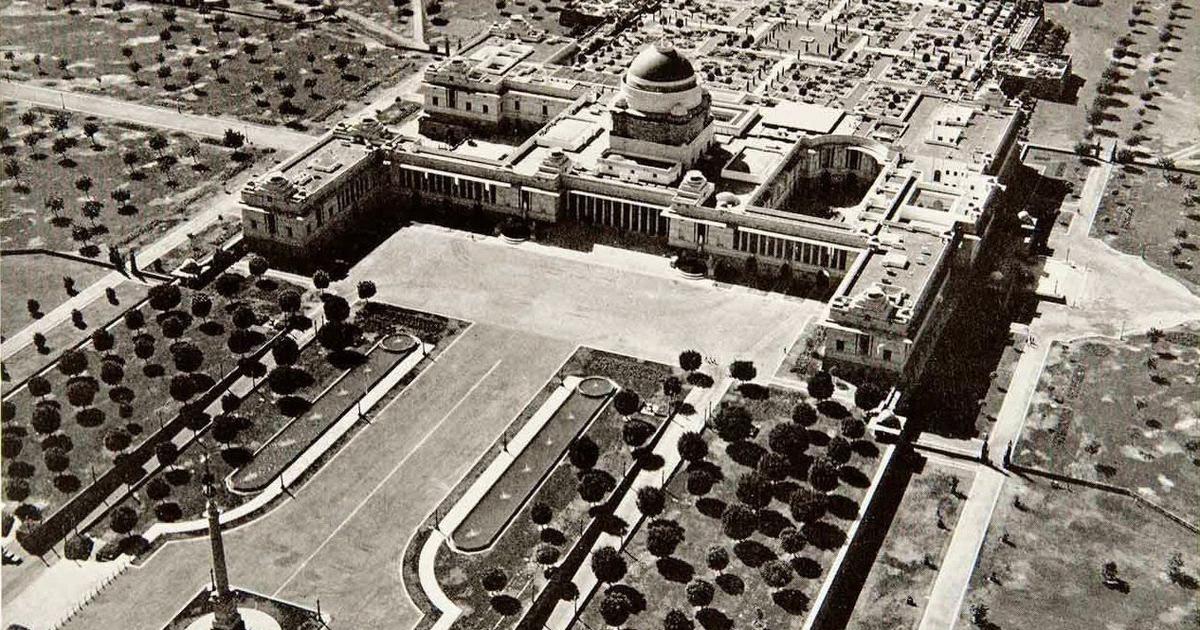

Working continuously from 1912 to 1930, Lutyens and Baker planned the city of New Delhi that despite its symbolism had no resemblance to its past. However, no one could deny the grandiose, the magnificence of the new capital established, the heart of which is fondly called “the Lutyens’ Delhi”. A vast rectangular mall is set out along the axis of the city that is surrounded by government offices (North and South blocks) and crowned at its far end by an imposing palace for the viceroy (now the Rashtrapati Bhawan). Tree-lined streets radiate from the central vista and converge into hexagonal nodes giving the area an unforgettable charisma. The boulevards are dotted with magnificent white bungalows for colonial administrators (now government officials). These bungalows have collonaded verandas and lush gardens that have charmed the people for nearly a century. This area is often called “Lutyens Bungalow Zone”, although the fact is that Lutyens himself designed only a handful of these structures.

Lutyens created a complex of extraordinary scale and unique picturesqueness, reflecting baroque classicism. One-third of the area was classified as “green zone” to give New Delhi the openness and elegance that sets it apart from the Old Delhi areas. Like the jewel in the crown, sitting on top of the Raisina Hill is the Rashtrapati Bhawan. The Rajpath (the elite passageway) connects India Gate to Rashtrapati Bhawan, while Janpath (the commoner’s passage) connects the South End Road (Rajesh Pilot Road) to Connaught Place. The two secretariate buildings and two magnificent cathedrals add to the glory of the design.

A near fiasco

Not everything went according to plan, though. The original concept of Lutyens’ Delhi was “from ridge to river”, that is, its expansion was planned from Raisina hill to river Yamuna. That was not to be. Again, there was a rumoured controversy about a bitter dispute between the two architects, Lutyens and Baker. Lutyens, as you would know, designed the Viceroy’s palace (Rashtrapati Bhawan) while Baker created the designs of the North and the South blocks, and he was the master planner, too. It’s said that the original plan was to design the slopes in a way that Rashtrapati Bhawan would be clearly visible from India Gate. But it seems Baker got his calculations wrong. You would only see the North and South Blocks from India Gate, but you would have to go virtually on top of Raisina Hill to have a clear view of the magnificent Rashtrapati Bhawan.

Lutyens’ design hasn’t been without controversies. Critics often dub it as a combination of western architecture with ancient Indian architectural elements that lack the real substance, a soulless design, it’s often referred to as. Time and technology and the rapidly growing population also bring their own challenges. We welcome readers’ views as an ambitious renovation plan has already been launched by the government.

Our next post will deal with the modern architecture taking place in the capital city after the independence. It would be great fun if the readers come up with a list of buildings and architects they would like to know about.

About the author

About the author

Sandeep Singh is an architect from IIT Roorkee. He is a prolific writer and a sensitive poet. His professional posts mostly cover the future in Architecture. His books are chiefly devoted to the inner and outer battles that a disabled person in India faces every day. His poems mostly reflect his inner world. He also works with the “Safe in India Foundation”, a social change initiative that strives to bring qualitative change to the lives of the Indian worker’s community